Iraq

Table of Contents

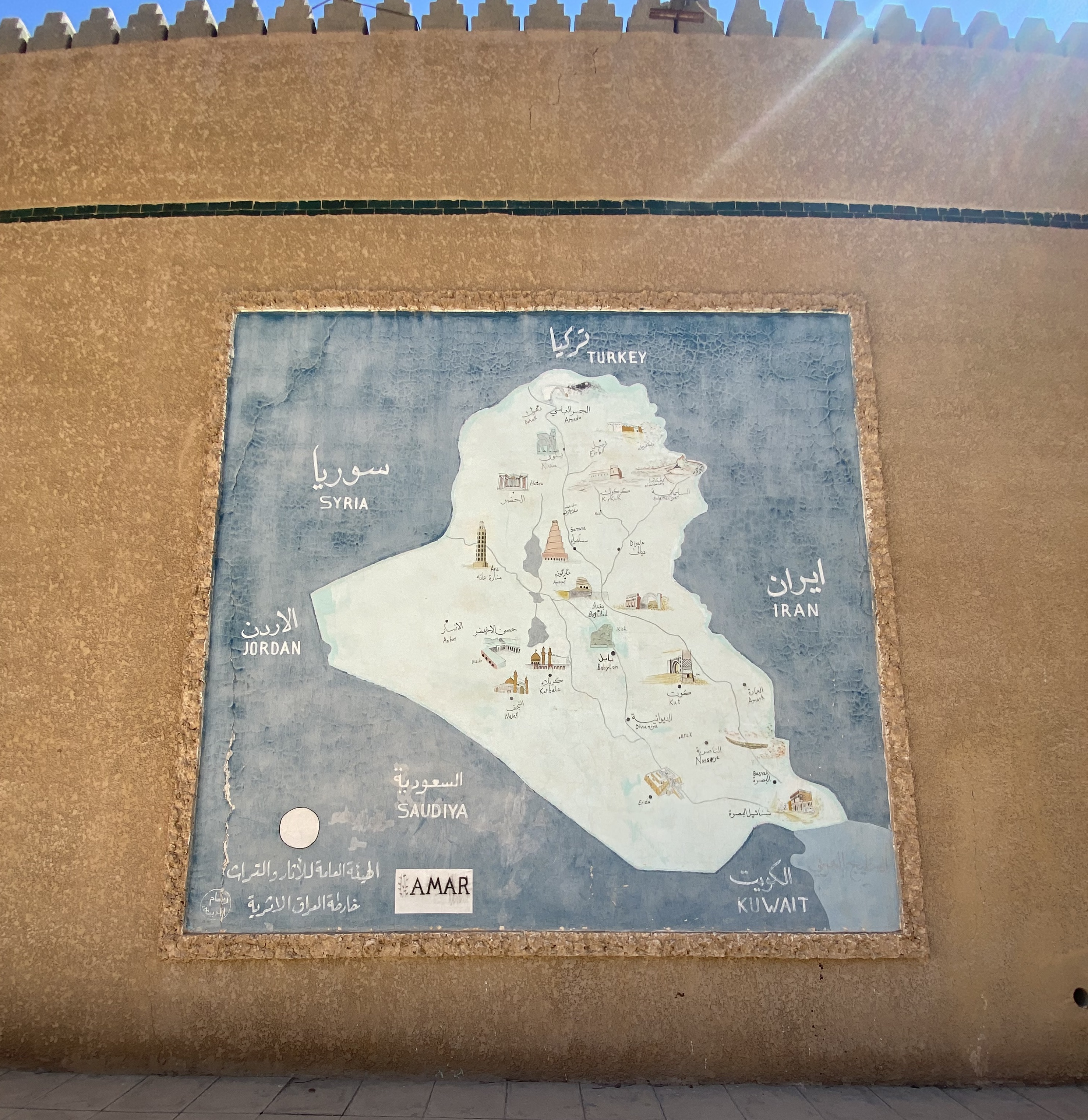

Detailed map of Iraq, highlighting major regions and cities. Taken in Babylon, 2021.

There's the Iraqi saying of "ماكو شبر", meaning "there isn't an inch". Given Iraq's size, I've visited every major city and have lived in every major region, from the river town of Hit to Basra and to the northern Turkish border. Which means it is time to make an assessment.

During my time in Iraq, from August 2021 to May 2023, my feelings about the country evolved into a complex mix of emotions. Initially captivated by its rich cultural landscape, my experience eventually led to a sense of jadedness, prompting my departure to Uruguay.

I previously wrote a thesis on Shia rituals in Karbala, one of the two shrine cities, which you can read here. I've also got a few other writings about Iraq, but this post is dedicated to my personal reflections on living in Iraq.

One of the most fundamental things one needs to understand is how young the Iraqi population is. Over 50% of the population is under 25 years old. With ~40 million people, this means that half the country was born around or after the 2003 invasion. They have grown up in the bones of the shattered infrastructure that the Americans left behind, which has been even more destroyed between the subsequent sectarian warfare and the fight against the Islamic State. It is impossible to understand the Middle East, and Middle East movements and revolutions without keeping this in mind.

1. South

1.1. Baghdad

"بغداد السلام ترحب بكم" - "Baghdad welcomes you"

While there are many foreigners in Baghdad, most of them are confined to the Green Zone, where the ones who remain there are basically locked in their compounds, and rarely leave because of kidnapping risk. Baghdad remains a strange place, when I was living there, I felt that the security situation was completely fine if you had your wits about you. Kidnapping risk remained low, and plenty of foreign tourists have been streaming in, eager to make an attempt at becoming some kind of traveler influencer1.

Baghdad itself is a massive city, unofficial counts place the city at 10 million people2. The city is divided by the Tigris river, which the Baghdadis have an interesting relationship with. As compared to Egypt, where life is centered around the Nile, and being close to the Nile, most Baghdadis have a standoffish relationship with the Tigris: they prefer to admire it from afar. When the Egyptians jump into the Nile and swim in it, I rarely found an Iraqi willing to even approach the banks of the Tigris.

Baghdad is also horrifically polluted, the city infrastructure hasn't been upgraded since the Saddam era, when population has exploded. Combined with sandstorms, you'll often find many people that have trouble breathing on some days, the pollution reminds me of Beijing in the worst era.

The division between the wealthy and the poor is also stark: rich areas, such as Mansour and Karrada, have far better electricity than the poor areas. Housing prices have skyrocketed even as infrastructure has stalled, million dollar homes are being sold on roads with pavement falling apart. Investment is flowing into Iraq, and much of it is being funneled into Baghdad, but only a trickle seems to make it into public infrastructure.

The Dora oil refinery, situated in the southern neighborhood from which it gets its name, continues to operate today. The refinery, however, is still within city limits, sitting on the banks of the Tigris and only kilometers from people's homes. The refinery itself has a complicated history3, but its operation until today is a metaphor for Baghdad: aging and creaking, but still alive.

For all its faults, I'm enchanted with Baghdad. The city is a struggle, yes, but it continues to breathe and try, people's lives are alive in Baghdad, with diversity in every neighborhood. I went and took friends to Sufi tekkiyas, Shi'a pilgrimages, tombs of Sunni scholars, and went all over. Late nights in Baghdad are always enjoyable, summer days are too hot, so during the summer Iraqis shift their schedule to be more at night. I spent many nights hanging with friends in Abu Nawas, in a section that a bitter Iraqi once described as "a ghetto", which is where this blog derives its name from.

Baghdad's diversity is its strength: Christian communities remain in Baghdad, aspirational youth try to make their way through the belly of the great beast, and the mixture of people within the city continues to push it forward. It remains the only large cosmopolitan city in Iraq with a sense of life, compared to the more staid Kurdish north.

1.2. Karbala

A religious ritual inside the Shrine of Imam Hussein.

My time in Iraq was largely focused on a single group of people: the Shi'a, specifically the religious ritual of radat. This ritual was developed in Karbala, one of the two holy shrine cities for Shi'a Islam within Iraq, about an hour south of Baghdad. Karbala is a small city, with around 1.2 million people, although this number swells greatly during pilgrimage season, which is denoted for two days: Ashura, the 10th day of the Islamic month of Muharram, and Arbaeen, which is 40 days after Ashura. Between these dates, millions of pilgrims descend onto Karbala, offering their prayers, hopes, and entreatments. The only thing I've experienced on this scale was Chinese New Year migration in China, which constitutes the world's largest migration of people, although the big difference is that China has the infrastructure to cope with this, whereas the Iraqi state barely does, meaning that the people step in to pick up the slack.

The city of Karbala is built on the site where the Battle of Karbala happened. In short, Hussein, the grandson of the prophet Mohammad, rose up against the tyrant Yazid. Hussein, whose army has been betrayed by the people of Kufa, another nearby city, is horribly outnumbered while Yazid's army encircles him and begins to deny access to water. Hussein predictably falls in battle, has his head put on a pike, and has his head taken to Yazid. Any Shi'a child could tell you this story, and for the Shi'a, is not only a holy event, but a dramatic one. Like the sacrifice of Jesus, both the Arab Shi'a and Iranian Shi'a perform plays to reenact this, for the Arabs this is called tashabih, for the Iranians it's ta'ziyeh. On ta'ziyeh, Hamid Debashi says4:

Ta'ziyeh remembers and reenacts a doomed battle between a small band of revolutionaries and an entrenched and deeply corrupt political power. There is a universality to the battle of Karbala that can easily be extrapolated to include any small band of revolutionaries fighting against any entrenched political power.

There's a certain aptness to the repetition of religious rituals, one of the most dramatic scenes I witnessed was when I first arrived in Karbala, seeing thousands of people in sync at a majlis inside the shrine.

I won't wax on too much more, you can read my thesis for a deeper analysis. Karbala the city is an interesting place, since you meet a combination of aggressive secularists to oppose the religious clerical class who are based in Karbala.

The main city center for Karbala is in a neighborhood called Hayy Hussein, which contains all the major shopping centers and a large boulevard. If you're ever around, I would suggest visiting Babil, which is the best restaurant in Karbala in my opinion.

1.3. Hilla/Babil, Najaf, Nasryiah, Basra

I've combined these cities into one section, not because I think they matter less, but rather because I've spent less time in them. Hilla, or Hilla/Babil, as the Iraqis call it, is a city on the site of old Babylon. You can still visit the ruins of Babylon, and walk through Saddam Hussein's palace that overlooks the Babylon complex. My friend and I snuck in some beers to relax after a hot summer day here once.

Hilla is a small town, nestled halfway between Najaf, Karbala, and Baghdad. Traveling south from Baghdad, you pass through Hilla, and then fork to either shrine city. As a result, Hilla is a crossroads for travel, but to me was largely unremarkable.

Najaf is the Shi'a center of learning in Iraq. In opposition to Qom in Iran, Najaf hosts seminaries on every street, as well as a massive holy graveyard. Interestingly enough, Najaf has also recently become the site of various (relatively) progressive secular NGOs, who advocate for a clearer distinction of power between the clerics and the government, in opposition to the Iranian model. However, Najaf faces a few political headwinds on all sides, as the Shi'a have settled into power, they've also become entangled with the government in ways that may make it difficult for them in the future, notably, they have refusal power on a cabinet seat 5. On the other hand, religious ritual changes after 2011 have gradually shifted towards the laity, and clerical jostling for power, especially between the Hashd al-Shaabi and the Sadrists have placed Najaf in an uncomfortable position. It's anyone's guess as to what it could look like in the future.

Najaf the city, however, is very odd. The proximity of Wadi Salaam makes the city feel extremely weird, and in my personal opinion, the tomb of Imam Ali is much more difficult to access than the shrines in Karbala. The shrines themselves have significant differences as well, while Imam Hussein and Abbas have a courtyard between them, they resemble massive mosques, fully enclosed, while Imam Ali has an open air courtyard. Outside of the shrine, the city functions as you would expect any regular city. Even though there is a Karbala/Najaf rivalry for Shi'a faithful, Shias around the country will make pilgrimages to both sites normally. Arbaeen, the holy pilgrimage, is considered most holy when walking from Najaf to Karbala, which I did in the August heat of 2022.

Further to the south lie the cities of Nasriyah and Basra. Nasriyah is the closest city to the famous Iraqi marshes, which were drained under Saddam during the Iran-Iraq war, and refilled later. The marshes are incredible, the Marsh Arabs who live there still preserve an old set of practices, sticking to buffalo farming and other subsistence agriculture. The marshes preserve a biodiversity not seen in the rest of Iraq.

Like in all of Iraq, there are some land disputes. While some people living in the Marshes mentioned to me that they would like to see the marshes preserved against climate change, which is ravaging the marshes, others mentioned that they would like to see them refrained, as they were granted سندات, which are land grants or deeds under Saddam. With the marshes currently filled, those with سندات cannot farm on them.

Basra is the only port city of Iraq. The Basra port is owned in large part by a Korean corporation, and the province of Basra is one of the largest oil production regions within Iraq. Paradoxically, Basra province is also one of the worst in terms of life expectancy and quality of life. Oil flaring, belches out carcinogens into the atmosphere in Basra, driving outside of city limits means that you see towers of flame throwing pollution up into the atmosphere.

Oppressively hot and humid in the summers, Basra used to be quite a party town. My friends recalled how when they were soldiers in the Iraqi army under Saddam, many of them would drive to Basra for the nightlife. Nowadays, Basra has returned to a version of its past. The nightlife, especially along the corniche, is quite nice, but Basra also remains a stronghold for various militias.

2. North

There's two types of foreigners in Iraq: the ones who have a screw loose, and the ones that wander in. The vast majority of the foreigners are in the Kurdish north, which I'll refer to as Iraqi Kurdistan or the KRG. The KRG has three major cities: Duhok, Erbil, and Sulaimaniya, which are split between the two political powers: the KDP and the PUK. The history is incredibly complex, but the biggest thing to understand is that while both sides hate each other, they've monopolized all power in the region to become a duopoly of power, the biggest oppressor of the average Kurd is not the Turks who conduct airstrikes in the north6, not the Iranians who lob missiles from the east, but rather the joint oppression of the KDP and the PUK. Despite all this, American security combined with lucrative negotiations with the Iranian government has turned Kurdistan into what a friend called "an American-Iranian joint enterprise", perhaps the first of its kind.

Erbil is a bizarre mixture of both types of foreigners. For example, you can end up at a place like the Grill, the Vinery, or the Sheraton Pool, where you'll mingle with defense contractors, NGO workers, and journalists. These places are interesting at first, but usually devolve into the same types of conversations after a little bit, and things can begin to feel a little frat or college-like. The academics, on the other hand, are all a little depressed. The effect on locals is different too, Erbil has grown to become basically a foreigner's town, with tons of money catered towards foreigner tastes. Sitting on the fault line of the KDP and the PUK, who seem to disagree on everything except one thing: investment in Erbil.

Erbil's real estate market is also tremendously warped. Since Erbil has been relatively stable compared to the rest of the country, rich Iraqis have long been stashing money by investing into large real estate projects.

Investment has made Erbil a boomtown, with tons of new construction going up everywhere. Unfortunately, the city is structured like a 12 year old playing SimCity, meaning it's hideously unwalkable, and has strange amenities plopped everywhere, including a golf course that required diverting water from wells that were actively being used.

Duhok is probably the most livable city in Kurdistan. Nestled in the only nice natural part of the north, Duhok is small, but quite livable. I stayed for a few months learning Kurdish, and I enjoyed my time there. Friends who are independent film makers in Duhok repeatedly tell me that Duhok is far better for artists than Erbil, where most of the work is concentrated in propaganda channels. It's no wonder that the Duhok Film Festival, the only festival of its kind in the region, has found great success in recent years. Duhok also remains the only major city on the way to northeast Syria, a population destination for NGO workers. I met and made a great number of good friends who work in Syria during the week, and return to Duhok for the weekends.

View of the valley from the Duhok Dam. Taken in 2021.

Sulaimaniya is the cosmopolitan capital of the KRG. While Erbil is similar to Dubai and has a similar soullessness, and Duhok is a city surrounded by nature, Sulaimaniya is a big city. It's beautiful, and holds a ton more cultural diversity than the other two cities. I've had fun whenever I went to Suli, but I never stayed there for a long time.

Kurdistan as a whole is in an interesting place. The politics have started to become apparent that the PUK have become sidelined, the future has become a little bit more unclear as the KDP collaborates with Turkey frequently. Baghdad's perpetual crisis seems to have eased up a bit, which has then drawn the federal government's attention back to Kurdistan. NGO money also seems to be on the outs in some cases, when the war in Ukraine broke out, I witnessed a ton of the demining NGOs pull up stakes and move up to Europe. Missionaries are everywhere in the KRG, I can't board a plane to Erbil without chatting up a missionary at this point.

Refugee management is also in a strange spot. The Kurdish government has largely used Syrians as a cheap source of labor, seeing the crises in Syria spigot to be managed. This means that the border crossing between Syria and Iraqi Kurdistan is repeatedly closed and reopened, often without any forewarning. However, given the state of infrastructure, most NGOs that work out of Syria still need to base themselves in the KRG.

Furthermore, Syrian refugees receive residence cards valid for a year, as a result of negotiations between the UN and the KRG. However, Iraqi Arabs, who come from places in the South such as Baghdad, receive one month residencies. This means that, without a visa sponsor, Iraqi Arabs who come to Kurdistan can be arrested by the Kurdish internal security, called the Asayish. The Asayish frequently use this as a way of intimidating Arabs from the South. The internal controls between the KRG and Southern Iraq pose another issue, an almost Hong Kong/Macau like situation is imposed upon people, although in HK/Macau the situation is far more formalized, with HK and Macau citizens having a different passport. In Iraq, both Kurds and Arabs hold Iraqi passports, but there is no free movement of people between the north and the south.

Within the KRG, there remain two other complicating factors: religious minorities and the PKK. The KDP arrangement with the Turks has made it so that the PKK are not allowed in most areas, except for one major region: the Nahla valley. The Nahla valley is situated near Duhok, and it is fully controlled by Assyrians. Assyrians themselves hold a complicated relationship with the Kurds. While they are spread out between Erbil and Duhok, some Assryians have fully integrated themselves into the Kurdish lifestyle in Duhok, while others in the Nahla valley hold onto an almost separatist ideal. As a result, there is a gentleman's agreement in the Nahla valley: because the Assyrians in the valley hate the KDP, they allow the PKK to use the valley as a staging ground for operations against Turkey. Turkey, as a result, frequently lobs drone strikes or missile strikes into the valley.

When I visited the valley, it was the first time I had seen so many bombed out roads within the KRG. Normally, Turkish airstrikes are limited to the far north, which are off paved roads and distant villages. However, it's impossible to enter the valley without seeing the destruction the Turks have caused, to great harm as well.

The Iranian-American joint enterprise is aggressively neoliberal, with smuggling rife from the KRG into Iran, and money is the key differential between many people. Foreigners who are holed up in compounds and Syrians and Iraqi Arabs homeless in the streets are a common sight. Many of these foreigners, especially in cities like Erbil and Duhok, use the KRG as a base for their travels to Mosul or into Syria – regions that, despite their challenges, continue to draw international attention and intervention.

2.1. Mosul, Sinjar, Kirkuk

Mosul is seeing a massive boom. Tons of reconstruction money is pouring in, alongside new businesses and a desire for regeneration has made Mosul one of the more interesting places to be right now in Iraq. Plenty of NGO reconstruction money has also made it a focal point for academics, and its relative safety compared to Baghdad has given the city a particular type of freedom. Sadly, I never managed to spend much time in Mosul, since it was outside my range of study.

I spent a few days in Tel Afar, around Sinjar mountain. Tel Afar is (now) a Shi'a enclave within the Sunni province. While I'm generally quite happy-go-lucky with Iraq, the moment I stepped out of the taxi onto Tel Afar soil I felt like the land did not want me. I've never felt such malice in the land, and Sinjar's reputation for being a hot zone still persists. People in Tel Afar spoke to me about how after the 2008 truck bombing that occurred in a market, the Shi'a men in the city assumed the perpetrators were Al-Qaeada and embarked on a pogrom of reprisal killings in the city, killing or driving out many families, a problem that still lingers to this day. The entire area around Sinjar is what I would colloquially call "fucked".

Kirkuk is similarly problematic. Sort of the promised land for the Kurds, it was under KRG control until their disastrous independence referendum, which led to a humiliating retreat of the Peshmerga as the Iraqi government recaptured large chunks of the region. Kirkuk is not dangerous per se, and nowhere as dangerous as the areas around Sinjar are, but tensions are still relatively high in recent days. Tribal conflicts between Kurdish are still an ever present tension. Furthermore, the presence of the Shi'a Turkmen militia only adds another complicating element to the tensions there.

3. West (Anbar)

Out of all the regions in Iraq, I've been here the least. For me, "West '' Iraq is just Anbar. Ironically, the Euphrates basin is far less polluted than the Tigris, simply because less people are dumping into the river. Hit, a sleepy town along the Euphrates, is a beautiful city characterized by its waterwheels, a UNESCO heritage site that still is active today.

Ramadi has seen an explosion in the last few years. Rapid development, bolstered in part with financing from the central government, has turned Ramadi into a hip destination in the desert. Iraqi friends will often remark on how much Ramadi has grown, with new job opportunities popping up everywhere.

Each region in Iraq, whether it's the West, the North, or the South, has a completely different personality. Mosul and Kurdistan are overrun with NGOs and foreigners, while the South remains a no-go zone for foreigners. Kurds have a completely different culture than Arabs, while Anbaris fundamentally see their position in Iraq differently than the Shi'a majority of the South do. The North is dependent on foreigners, especially the Americans, and it's no surprise the Americans are building their second biggest Middle East State department compound in Erbil. Syrians are treated better in some ways in the North than Iraqi Arabs from the South.

Erbil, the political center of the north, has embarked on the world's worst sim city project, attempting to build golf courses, poorly constructed high density housing, all to try to appeal to the foreign population. A miniature Dubai, in all its excesses. However, in doing so, it has reaped massive benefits while the other cities have languished, Sulimaniya, previously a commercial capital, has fallen behind both economically and politically. However, the duopoly of power between the two parties have strangled economic growth to a certain extent, a system rife with nepotism and thuggary. Everyone knows that there is tremendous waste, huge bribes are paid every year for projects, with overinflated prices that make your eyes water. The two parties are enriching themselves at the cost of the Kurdistan region as a whole.

The South is sprawling, with constant infrastructure and demographic issues. Electricity remains worse, roads remain worse, access to medicine and everything else becomes more scarce with each passing year. Baghdad is creaking at the bones, choked with smog and a growing urban poor problem. Yet in spite of all of this, no such arrangement of power exists in the South like the North. In south Iraq, the complicated sectarian situation has created pockets of protests and progressive movements. I would argue that there is more freedom of speech within Najaf than in all of the KRG.

Anbar, which has retreated into the background following the defeat of Daesh, has also continually gone through its own crises. Anbaris remain distant from the rest of Iraq, distinguished from the Shi'a south and the Kurdish north. Politicians come out of Anbar and become almost gods, Halbousi7 was a practical god in Anbar, with his image strung up in every street corner and people talking about how much money he had brought in from the central government to redevelop Ramadi.

4. Electricity

A special note about electricity, since this is everyone's first experience in Iraq. Iraqis do have 24 hours of electricity, but the electricity is not consistent. At least twice a day you will switch between government provided electricity, which is very similar to electricity provided in a developed country, and generator (muwallad) provided electricity.

This means that you will have a giant belching generator in your neighborhood, with a generator mafia you pay a stupid amount of money to. This also means that for at least twice a day, you will experience a small blackout. Shorter blackouts mean that you are switching from generator to government. Longer blackouts mean you are switching from government to generator. Notably, you don't want to use an electric kettle on the generator, since you're limited on amperage. The image on the right was the electrical box in my house, responsible for telling you where the electricity is coming from and handling the switch. The arrow at the top that says "وطنية" means government electricity, and the others with "مولد" mean generator.

5. The Environment

A fellow PhD friend once mentioned that the media cycle of conflict and post-conflict zones goes from coverage of women + children, to only about children, to then being about animals, and finally about the environment before coverage dies completely. In recent years, the topic of the environment has become very hip to discuss in Iraq. NGO money has poured into climate change, as Iraqis themselves have invested in projects in an attempt to arrest the inexorable desertification8. The Marsh Arabs have become at the forefront of this, as desertification of the marshes is the most visible effect of climate change. International organizations, such as IOM, have engaged in climate change projects as a buffer against future refugee flows, assuming that if large chunks of Iraq become uninhabitable, refugees will start moving towards other countries.

On the northern side, the KRG has recently emerged as a small destination for rock climbing and hiking. Projects such as the Zagros Mountain Trail have popularized Kurdistan as a destination for hikers and climbers.

6. The Government

The federal Iraq government and the Kurdistan Regional Government have taken two separate tasks. As mentioned before, the KRG has taken the role of a duopoly in a politburo system, with large networks of patronage spread throughout. As the KRG has enforced and entrenched its oligarchic rule, the federal government struggles to maintain control. The KRG has what people call the "green zone" and the "yellow zone", representing the PUK and the KDP. The no man's land between them recently hosted a protest, where truckers piled up dirt mounds on the road to protest the poor conditions and lack of responsibility for infrastructure in the no man's land.

Checkpoints abound in Iraq, but the checkpoints in Iraq are honestly no different than the ones in the other Middle Eastern countries. There's a small cottage industry of foreigners who come to Iraq only to write about the checkpoints, and to me this is akin to coming to America and writing about toll roads. Checkpoints, so ubiquitous, fade into the background like the electricity problems.

A recent interesting change within the last decade has been new crackdowns on freedom of speech. While limited freedom of speech within the KRG has always been normal9, the new social media law passed two years ago has been used to arrest and detain people. The Iraqi Ministry of Information uses a crowdsourced app for people to report content that may be against the law.

Coinciding with this change in digital literacy is the growth in private enterprises. Salaries from the central government and the KRG have routinely been late, which has created a debt industry of people who provide loans until the salary is actually released. This system has been formalized with the growth of electronic payments such as the Qi card.

It's clear that with higher digital usage and electronic payments, combined with new real estate projects growing all over the country from Baghdad to Erbil, has made private investment much more lucrative. Business investment is up overall, but issues around clarity of contracts, such as the TotalEnergies oil contract in Basra, have perpetually made investment difficult, which the central government has routinely failed to simplify.

On top of the contractual problems in Iraq, both governments are simply corrupt. There's reams of literature on the corruption of the central government and the KRG that I won't rehash here, but needless to say trust in both governments is low among the population.

7. The Mess That We Find Ourselves In

Against the coming environmental disaster, the problem of governance, what is to be done?

The people make Iraq. Iraqis and their culture, despite the tidal wave of challenges they face, are fundamentally kind. This is hard to describe, but life in Iraq was the first time in my adult life where I existed outside of the direct confines of capital and its socially warping power. Iraq has a high trust Islamic society, where petty crime is almost unheard of, and the generosity of everyone I met made Iraq a truly magical place.

Iraq is also a place riddled with contradictions. By the end of my time, I had become quite jaded with the place, with a friend describing my writings similar to a "bitter secularist." I had taken to calling foreigners the corpse washers of Iraq, noting how the climate disaster combined with poor governance and a demographic explosion was leading up to a catastrophe. With the beauty of distance, I no longer think this. I think that there continues to remain hope for Iraq, but the window is closing fast.

Masgouf, a classic Iraqi dish composed of a split carp grilled over a fire.

Footnotes:

The vlogger types usually end up making videos with titles like "I went into militia territory!" or "Is Iraq safe to travel to?" The few that I've met traffic in stereotypes, they make the places not dangerous seem dangerous, and make places that are dangerous seem safe. It's a weird combination.

A proper census hasn't been conducted in decades, partially for sectarian reasons.

See https://chokepoint.substack.com/p/if-the-daura-refinery-could-speak for the history.

H. Dabashi, “Taʿziyeh as Theatre of Protest,” TDR (1988-), vol. 49, no. 4, pp. 91–99, 2005.

H. A. Hamoudi, “ENGAGEMENTS AND ENTANGLEMENTS: THE CONTEMPORARY WAQF AND THE FRAGILITY OF SHI’I QUIETISM,” J. law relig., vol. 35, no. 2, pp. 215–249, Aug. 2020, doi: 10.1017/jlr.2020.

Before he was unceremoniously sacked late last year.

I gave a talk at an academic conference in the University of Hewler and it was clear academics were swerving around particular questions.