What is a Scheduler Anyways?

Table of Contents

Last year, we had an outage that got detailed in the Linux Plumbers Conference: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KFItEHbFEwg, where a deployment of Lavd broke the Erlang runtime that had CPU pinning enabled.

As part of this, I wanted to learn more about the interplay between these two systems. sched_ext1 is here to stay, and growing, and I expect it to only get more important as time goes on2. Runtimes are also getting more sophisticated: Fil-C is building a memory safe C runtime, Python might be finally losing its GIL and getting a JIT3, and Go is seeing ever more adoption. As these runtimes layer their own scheduling on top of the kernel, the cross-interactions between the two create second order effects that are hard to predict. This post is about one of those.

1. So What Happened?

We pin CPU cores for Erlang schedulers on WhatsApp in order to get more performance. An Erlang scheduler is an abstract worker that can process arbitrary units of work. Traditionally in Erlang, after 4000 reductions4, the schedulers will swap away from the current task and give another task a chance to run.

Schedulers can be configured to be bound to particular CPUs using the sbt setting, which has many options around NUMA, hyperthread spreading, etc. As a bit of foreshadowing, there is a very interesting note in the documentation:

Suddenly one day we had absolutely garbage P99 response times. This took us a while to debug, but ultimately with the help of various people we were able to pin it down to Lavd5. So this gives us a good place to start: why the hell does lavd muck up my cpu affinity?

2. Lavd

Luckily for us, lavd has excellent public documentation: https://github.com/sched-ext/scx/tree/ad30a290a1531987a434e034e2ab2307880a4a11/scheds/rust/scx_lavd

The first paragraph gives us a good explainer (emphasis mine):

scx_lavdis a BPF scheduler that implements an LAVD (Latency-criticality Aware Virtual Deadline) scheduling algorithm. While LAVD is new and still evolving, its core ideas are 1) measuring how much a task is latency critical and 2) leveraging the task's latency-criticality information in making various scheduling decisions (e.g., task's deadline, time slice, etc.). As the name implies, LAVD is based on the foundation of deadline scheduling. This scheduler consists of the BPF part and the Rust part. The BPF part makes all the scheduling decisions; the Rust part provides high-level information (e.g., CPU topology) to the BPF code, loads the BPF code and conducts other chores (e.g., printing sampled scheduling decisions).

So we have a BPF thing that polls and gets scheduling information, and then we have a main.rs that binds CPU topology. Neat. Before we go further, we need to understand what lavd sits on top of. We are in EEVDF land for the Linux scheduler now, which has completely replaced the old CFS scheduler. So forget your time quanta, now you need to think about lag6.

In the classical EEVDF space, we have a per CPU runqueue7. Specifically, the runqueue struct has this information:

struct rq {

struct cfs_rq cfs;

struct rt_rq rt;

struct dl_rq dl;

#ifdef CONFIG_SCHED_CLASS_EXT

struct scx_rq scx;

#endif

}

So, cool, we can see that there's a runqueue for scx (sched_ext) and a runqueue for eevdf (still called cfs). Given that it's per CPU, this means that each CPU maintains its own rb tree of runnable tasks8:

struct cfs_rq {

/* ... other not interesting stuff ... */

struct rb_root_cached tasks_timeline; // rb tree

}

So that's neat. This tree means that all the tasks on a given core only compete against other tasks on that same core.

Now if we look at lavd, specifically the scheduling mechanism9:

static u64 calc_virtual_deadline_delta(struct task_struct *p,

task_ctx *taskc)

{

u64 deadline, adjusted_runtime;

u32 greedy_penalty;

/*

* Calculate the deadline based on runtime,

* latency criticality, and greedy ratio.

*/

calc_lat_cri(p, taskc);

greedy_penalty = calc_greedy_penalty(p, taskc);

adjusted_runtime = calc_adjusted_runtime(taskc);

deadline = (adjusted_runtime * greedy_penalty) / taskc->lat_cri;

return deadline >> LAVD_SHIFT;

}

We can see here that there's a notion of "latency criticality" and "greediness." A higher latency criticality gives a tighter deadline, and the greedy penalty ensures fairness while scheduling.

Lavd's Rust handoff code is in main.rs, where scheduler::run() is the handoff to BPF. If autopower is on, we poll the system power profile and then push to BPF, and then process stats.

The BPF code then wakes up, and performs this gigantic list of operations:

SCX_OPS_DEFINE(lavd_ops,

.select_cpu = (void *)lavd_select_cpu,

.enqueue = (void *)lavd_enqueue,

.dequeue = (void *)lavd_dequeue,

.dispatch = (void *)lavd_dispatch,

.runnable = (void *)lavd_runnable,

.running = (void *)lavd_running,

.tick = (void *)lavd_tick,

.stopping = (void *)lavd_stopping,

.quiescent = (void *)lavd_quiescent,

...

You can look at the individual functions, but:

lavd_enqueue()calculates the virtual deadline, and inserts it into a queueing structure called the DSQ.lavd_dispatch()pulls work from the DSQlavd_running()calculates the time slices, and advances the logical clocklavd_tick()has some very key logic that checks if there is any higher priority task left in the DSQ. If there is, it shrinks the current time slice to give the higher priority task a chance to run, effectively yielding the current task.lavd_stopping()is a cleanup oplavd_quiescent()handles various sleeping stats

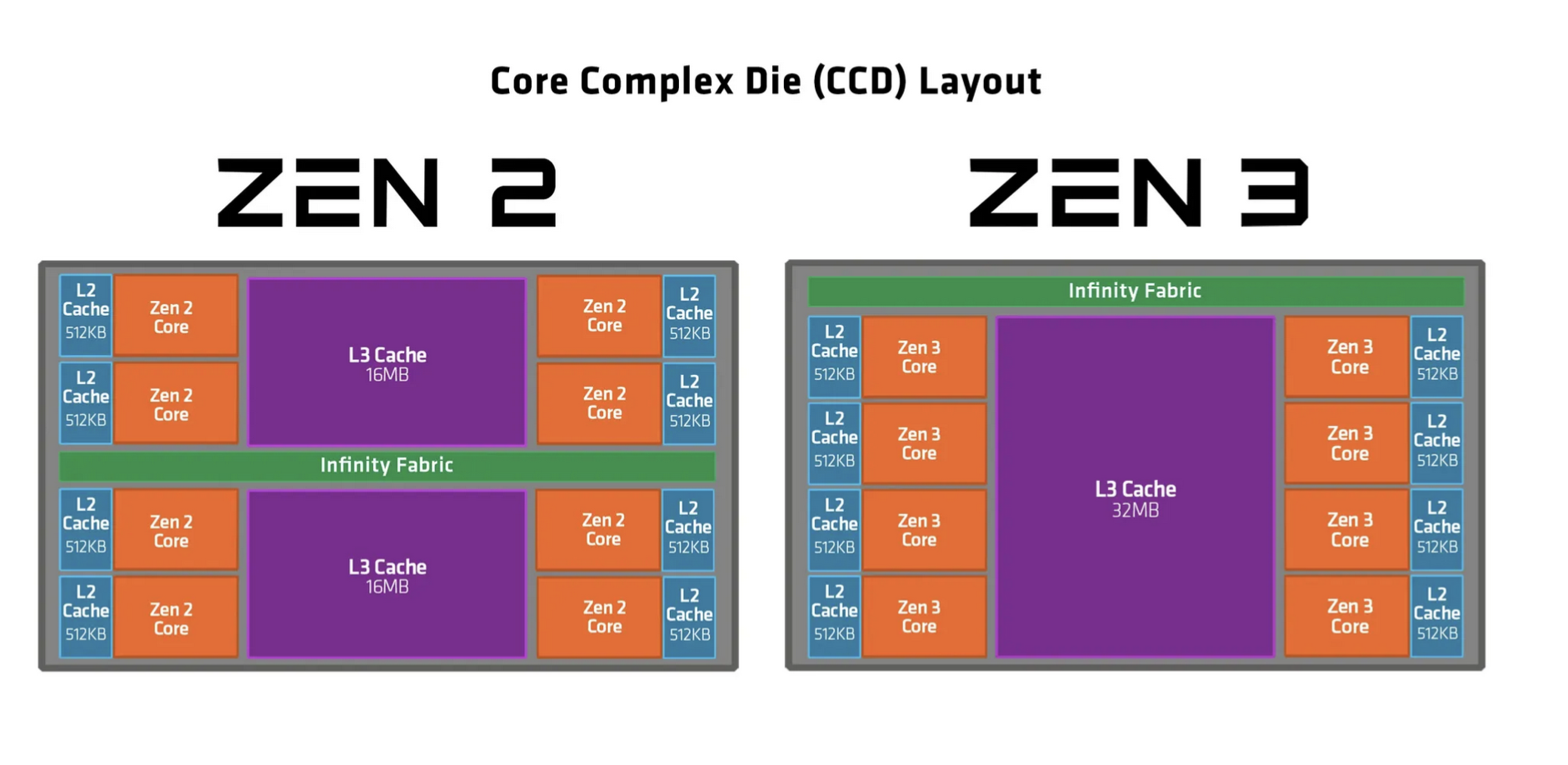

So critical to this entire system is the concept of a DSQ (dispatch queue). Unlike EEVDF's per-CPU runqueues, a DSQ is shared across multiple CPUs, arranged either by the last level cache (LLC) or an AMD core complex (CCX).

For example, you can think of a traditional CPU with 4 cores, each with their own L1/L2 caches but a big shared L3 cache as sharing one DSQ. This is a more traditional CPU:

However, with the rise of AMD's packaging, we've effectively added a newer interconnect called the "Infinity Fabric":

So this means that for older, Intel chips, they'll have a single DSQ for all their cores on the CPU, while newer AMD CPUs will have multiple DSQs, one for each CCX.

3. Erlang Schedulers

We now need to take another digression into how the Erlang (BEAM) scheduler works. We talked about this briefly at the start, but I'll go more into detail here.

The BEAM scheduling mechanism is divided into subsystems called schedulers11. There is typically a single scheduler per core, and each "scheduler" is really an OS thread that acts as a worker, doing some amount of work before switching to another piece of work12. From the Linux kernel's perspective, each Erlang scheduler is just another thread to be scheduled. Because Erlang is an actor based programming paradigm, this ensures that each actor only gets a particular amount of CPU, before yielding to another actor. Erlang uses a dimensionless metric known as a "reduction." A reduction roughly maps to a single function call, and because Erlang is a functional programming language, you're guaranteed to have to make some function calls at some point13. After a specific amount of reductions (4k as of writing), the scheduler switches14.

Because the BEAM has cascading schedulers, this fixed reduction count means that when a scheduler has a bunch of stuff queued up and it doesn't execute, then it piles up the work. Unscheduled schedulers (heh) also cannot have tasks stolen without cooperation from the victim scheduler.15

Now, as with any scheduling system, we need to implement some form of task stealing. If scheduler A is running something and has a big queue of work while scheduler B has nothing to do, it surely makes sense to allow scheduler B to pick up some of the slack. Erlang does this with single task stealing, which means that a scheduler steals a single task from another scheduler's runqueue after the victim scheduler has acknowledged it16, 17.

4. The Problem

Phew! We've finally gotten to the actual issue!

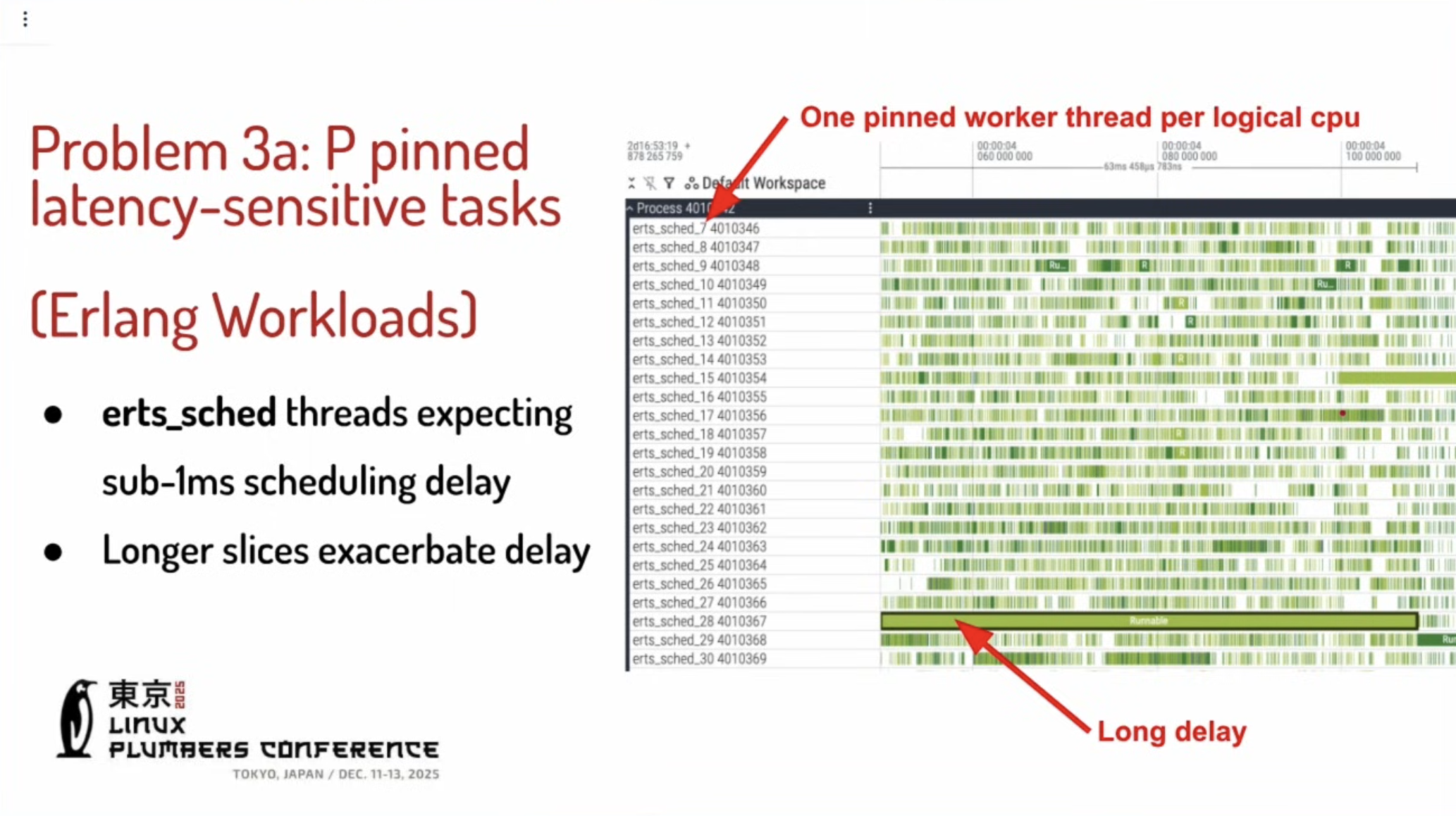

At the start, I mentioned that we bound Erlang schedulers to specific CPUs, pinning specific schedulers to specific cores.

Remember that the Erlang scheduler thread has CPU affinity set, so it can only run on, say, CPU 3. But lavd didn't have per-CPU queues at the time. It dumps the thread into the shared LLC DSQ alongside everything else. So the Erlang scheduler thread only gets picked up when CPU 3 happens to pull from the front of the DSQ, which might not be for a while.

This also causes head-of-line blocking. When CPUs 0, 1, and 2 scan the DSQ for work, they find the Erlang scheduler thread sitting there, pinned to CPU 3 and useless to them. They have to iterate past it. Not catastrophic on its own, but it compounds.

In Erlang land, because Erlang schedulers cannot steal tasks without the acknowledgement of the victim scheduler, starving a particular Erlang scheduler means that its runqueue is effectively frozen. Even worse, this creates a second order effect, where:

- Lavd would finally allow the BEAM scheduler to run

- The BEAM scheduler runs for a very long time, exceeding the amount of time it's allocated, because it has so much work to do and hasn't been able to offload any of its work to other schedulers

- Exceeding this virtual deadline means that lavd naturally pushes back the BEAM scheduler further back into the DSQ, due to the greediness penalty.

- Because it takes so long for the BEAM scheduler to get a chance to run again, it builds up so much work that it exceeds the virtual deadline even further, worsening the situation!

Now this situation was less serious on AMD chips, because multiple CCXs meant multiple shallower DSQs, so the BEAM schedulers got to run more often. However, on machines with a single LLC, this meant that a fat DSQ could cause the BEAM schedulers to get shoved way into the back of the queue.

This was fixed with per-CPU DSQs for Lavd, which is conceptually simple. But the outage wasn't caused by any single bad decision. Erlang's CPU pinning is reasonable. Lavd's shared DSQ was a reasonable default. The greediness penalty is a fair scheduling mechanism. Each layer was doing something sensible in isolation. The problem is that runtime schedulers and kernel schedulers are mostly unaware of each other, and when their assumptions collide, you get feedback loops that neither system is equipped to break.

Footnotes:

As the GPU goblins start stealing my electricity from below, and the death of Moore's Law eats us from above, application developers like me have to retreat back to specialization: eeking out more performance out of what we have.

https://peps.python.org/pep-0744/. Also check out Xu, Haoran, and Fredrik Kjolstad. “Copy-and-Patch Compilation: A Fast Compilation Algorithm for High-Level Languages and Bytecode.” Proceedings of the ACM on Programming Languages 5, no. OOPSLA (2021): 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1145/3485513.

Another unit of work for Erlang. A reduction is roughly a function call. Compare this with Golang, which gives every goroutine around ~10ms of runtime before swapping to another.

The Linux plumbers video gives a bit better explanation about how the Linux team @ FB tested lavd.

I know, kind of terrible naming.

There is also a concept of a "dirty" scheduler, meant for running io bound tasks. We will ignore these for now, but they are meant for longer running applications beyond the 4k reduction limit. See https://blog.stenmans.org/theBeamBook/#_implementing_a_simple_nif.

I was trying to find a good blog post that explained this more in detail, but honestly https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=13503951 was the best point. There's a ton of annoying blog posts that call Erlang a preemptive scheduler when it's really a cooperative scheduler with yielding on the reduction counts

This is all implemented in erts_schedule() in erl_process.c.

The BEAM also uses sched_wall_time_change() to determine scheduler transitions. Starved schedulers are still considered active, so the BEAM stops scheduling new work onto them and encourages other schedulers to steal from their queues.

If you're coming from Rust, this might sound very familiar to the Tokio task stealing mechanism, where every OS thread acts as a worker. When the worker threads run out of work, they search the global queue, and if that's empty, they attempt to steal half the tasks from top of a peer's queue. Erlang's task stealing mechanism is indeed very similar!